One early morning in April 1878, a 20-something Polish youth climbed into a boat to board a British ship, James Westoll, moored some distance from the shore. As the boat neared the liner, a husky voice from the deck above growled: “Look out there.”

Those three simple words were enough to touch the young man’s heart and bring tears to his eyes. It was the first time in his life that someone had addressed him in English–the language of his “secret choice”, of his “future”, of his “very dreams.” The world was to remember him as Polish-British writer Joseph Conrad.

Conrad’s love affair with the alien tongue began very early. He was first introduced to it by his father, a minor poet with a great dream of translating the works of Shakespeare. At that time Conrad was barely eight years old. But by 12 he was orphaned and at the age of 16 he decided to break away from his roots and sail into the unknown. He remained a sailor for the next 20 years, having worked with French Mercantile Marine for the first four years and then joined the British Merchant Navy.

Those were harrowing years of uncertainty when he somehow became convinced of the fact that no other language could express as well as English. At night, when his co-sailors curled up in bed, he toiled over his favourite English & French writers, with an “unremitting, never discouraging” zeal.

In the early part of his massive reading programme, Conrad fed his growing imagination with classics of the French Masters, particularly Flaubert and Maupassant, and he felt impelled for the first time to put his tortured past on paper when he caught sight of the spot where the characters Emma Bovary and Rodolphe (in the novel Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert) had their tryst. Conrad had reached the point in life when he started living day and night with a divine dream of becoming a writer.

For that he owed a lot to Edward Garnett, a critic and a writer. In fact, Garnett was the inspiration behind Conrad’s first novel, Almayer’s Folly (1895), which had taken five agonizing years to complete. It was followed by An Outcast of the Island the following year. But the sparks of genius which leapt off the pages of these two novels seemed to dissolve as he made an attempt to write the next novel titled Rescue, which was left unfinished (he was to take up the abandoned project more than 20 years later in 1918, and the novel was eventually published in 1920).

“I can’t bear to look at the manuscript … Everything seems so abominable. You see the belief is not in me” he wrote in abject frustration. Conrad faced a serious dilemma: to write or not to write in a foreign language; and was on the verge of giving up his choice of English. At that time Garnett proved to be a big help. His words of encouragement worked wonders. They buoyed him up and instilled fresh hopes in him. However, the Englishman’s increasing interference with Conrad’s style of writing also had a negative effect on the budding writer’s sensitive mind.

Garnett’s comments such as “Construction is bad” and “perfectly rotten” touched a raw chord in the troubled author, who voiced his anguish thus “And understand well this: if you say “burn!” I will burn–and won’t hate you, but if you say: “Correct–alter!” I won’t do it–but shall hate you henceforth and forever!” No doubt, Conrad’s early writing did appear laboured but he wasn’t ready to take Garnett’s criticism lying down.

His faith in his ability to write in his most preferred tongue was finally vindicated with the publication of The Nigger of the Narcissus (1897). Conrad wrote this novel at a time when he had nearly reached the end of his tether. People showed scant respect to his identity as a writer and at 40, his future appeared bleak. But the Muse descended right in time to soothe his overtaxed mind. He let the story about the nigger flow out of him, simply, without resorting to “theories” or “formulas” which according to Conrad were “dead things.” He wrote “straight from the heart –which is alive.”

Immediately after the publication of The Nigger of the Narcissus he penned a preface to it. A preface which in terms of literary quality and intrinsic value, surpassed Oscar Wilde’s preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray or Maupassant’s to Pierre et Jean. It is now regarded as the “preface of prefaces”, where Conrad spoke about the progression d’effect.

Although The Nigger of the Narcissus is a watershed in his writing career, it did not spell an end to Conrad’s complexes. He continued to worry and slog over the ‘shape and ring’ of his sentences. It was a rather difficult period, when he co-authored The Inheritors and The Romance with writer-critic Ford Madox Ford. But it did not help matters. Once again his faith in himself suffered a setback. “No. It’s no use. I’m going to France. I am going to set up as a French writer. French is the language. It’s not a collection of grunted sounds”, he wrote.

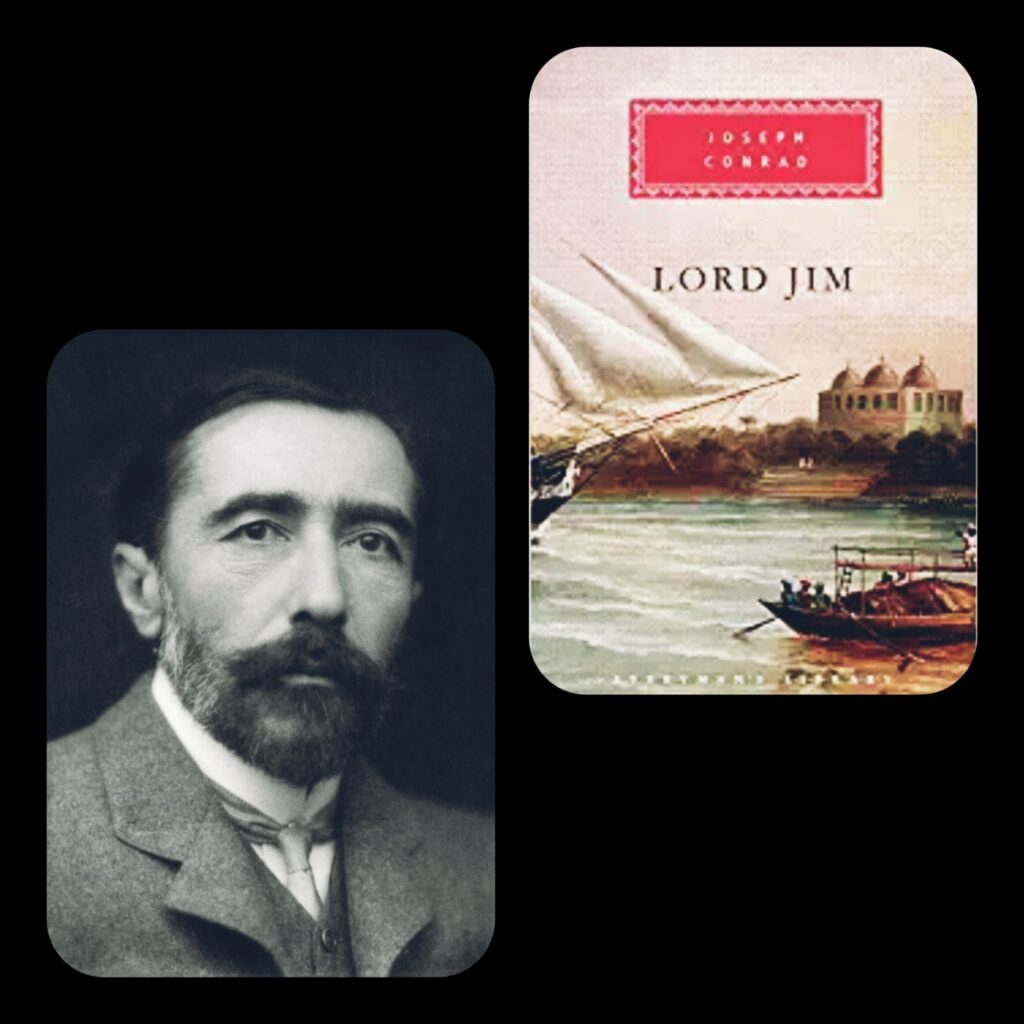

That, thankfully, remained a petulant outburst and nothing more. Conrad continued to work like “a coal miner in his pit, quarrying all English sentences out of a black night”, only believing in the truth of his own sensations and seeking refuge in the continuity of unrelenting effort. Success, at last, with its healing touch came “like a consummation in the end.” With the publication of Lord Jim (1900), Heart of Darkness (1902), Nostromo (1904), Chance (1913) and Victory (1915), to name some of his notable works, his reputation soared.

His acute poverty, the premature death of his father, Apollo Korzeniowski, who had been exiled for having taken part in the Polish nationalist uprising in 1863, his attempt at suicide and the turbulent emotional conflict born out of bizarre sea voyages provided material for his novels. In most of his novels, Joseph Conrad’s protagonist is a lonely man with a profound sense of guilt whose search for forgiveness leads to his final tragic resolution.

Authors like Graham Greene, William Faulkner, T. S. Eliot, H. E. Bates were, among countless others, indebted to him for his shifting and descriptive narrative style. Thus, he earned for himself a niche as a writer ‘more English than the English’. His desire to be understood, as the author himself said, “as completely as it is possible to be understood in our world, which seems to be composed of riddles”, was finally fulfilled.