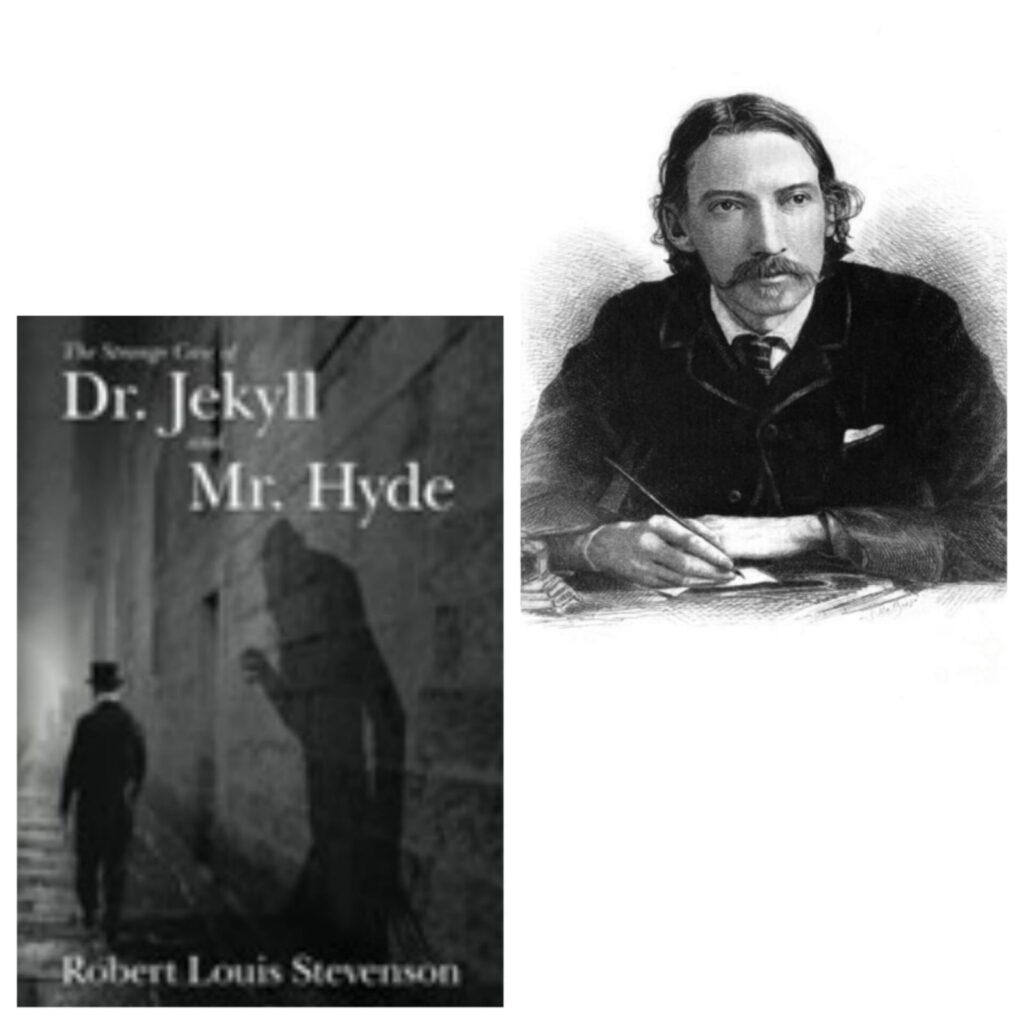

Robert Louis Stevenson

It was one early morning in Bournemouth in the year 1885. The mountaintops were concealed in the pre-dawn mist. Inside a cozy room in an old mansion in the small town, Robert Louis Stevenson was fast asleep. All of a sudden, Stevenson let out a series of piercing shrieks, which startled his wife, Fanny.

Sensing something terribly wrong, out of sheer fright, she brought him back to his senses, not knowing that she was doing more harm than good to her husband, who was in the process of dreaming a fantastic dream. Stevenson, immediately upon waking, flew into a rage and voiced his displeasure thus: “Why did you wake me up? I was dreaming a fine bogey tale!”

Reportedly, someone intruded into S T Coleridge’s privacy when he was all concentration trying to remember the lines that were supplied to him by the Muse in his dream. This sudden intrusion caused him, according to Coleridge himself, to leave the poem, “Kubla Khan”, unfinished.

However, Stevenson imposed shape and order on this truncated nightmare that, at first, defied expression. He went on to write The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr. Hyde which, to a great extent, helped him exorcise the ghosts of his temptation-tossed past.

Stevenson’s childhood was rather a happy one. He was born a frail child with tubercular trouble. Although he was everyone’s center of attraction in the family, he, even as a child, had an acute desire to be alone, so that he could lapse into a reverie, and then write all about it. This desire to be by himself was also encouraged in him by his nurse, Alison Cunningham, who, during bed time, regaled him with stories written by great masters. A Child’s Garden of Verses (1885) is reminiscent of the days he spent with his loving nurse.

Prior to his departure for the Edinburgh University, Stevenson had no real experience of the outside world, barring the few strolls with his father around the hills surrounding Edinburgh, the knowledge gained from the stories narrated to him by his nurse ‘Cummy’, and a fitful attendance at school. His father did not like his habit of scribbling, but wanted him to be a lawyer of repute. So Stevenson left for Edinburgh University to study Law. And then all hell broke loose.

In The Misadventures of John Nicholson (1887) one finds the evocation of a troubled youth in Edinburgh. There he started living an unconventional life. He visited ‘disreputable haunts’. He went on pub crawls. He wandered through nasty places ‘unpiloted’. His love affair with Claire Drummond (Flora Mackenzie in the story) also squeezed him dry. In Edinburgh, Stevenson, for the first time, confronted the vicissitudes of life that wooed him forth and warned him back again into himself. He got caught in a “dizzy seesaw, heaven-high, hell-deep”. Alienated from home, ostracized from Edinburgh society, Stevenson found himself at the mercy of his emotions.

The pulmonary trouble was, by this time, seriously aggravated by this ultra-bohemianism. He had, therefore, to leave for Suffolk in 1873 for recuperation. There he met one Mrs Sitwell who not only took great care of his health but also inspired him to write. During all these troubled years, one thing, however, remained constant for Stevenson — writing. He was then writing mainly essays that showed flashes of his genius. His writing skill was confirmed when magazines like Portfolio, Cornhill carried some of his essays.

The agony born out of the repellent settings of his youth was somewhat assuaged when Stevenson tied the knot with a ‘steel-true and blade-straight’ married woman. Immediately after having journeyed on a canoe through the waterways of Belgium and France in September 1876, he chanced upon Fanny Osbourne who was ten years older than him. From the very first meeting they became inseparable.

Mentally a bit relieved, Stevenson went on an essay-and-story writing spree. An Inland Voyage (1878), based upon his canoe trip, Essays and Travel: Travels with a Donkey in the Cevennes (1879), saw the light of day. His reputation soared.

Fanny at that time was temporarily staying in Paris with her children, taking lessons in painting in order to keep at bay the agonizing thoughts of an extremely unhappy marriage with an American, Samuel Osbourne. Fanny had to undergo a trying time before she could obtain the divorce and marry Stevenson, who was sickly and fragile. Fanny’s eldest son Lloyd reminded Stevenson of his own childhood days with his nurse. He suddenly felt the irrepressible urge to entertain Lloyd the way ‘Cummy’ had once entertained him.

Treasure Island, an adventure story, took shape. The whole world along with Lloyd quivered with excitement while reading the story. Treasure Island (1883), ranked as one of the greatest tales of adventure, put his name on every lip after the publication of the same, whose working title was The Sea Cook. Inspired by this phenomenal success, Stevenson wrote another long novel Kidnapped (1886), meant for the children, that won the hearts of children and adults alike. The publication of Treasure Island catapulted him to the top. But the echoes of yore, of the time when he revelled in the company of those who painted the town of Edinburgh red, kept haunting him.

Then a nightmare in the wee hours of a certain morning came to his rescue that suggested the plot of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde ‘in a series of small, bright, restless pictures’. Stevenson, that day, did not get up from bed for fear of losing the thread of the story. He wrote the first draft lying in bed at an incredible speed. But Fanny took a dislike to it saying that the characters were flat, and not allegorical. She urged him to make an allegory out of his nightmare.

Stevenson destroyed his first draft and set himself to writing the novel from an altogether different standpoint. So The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886)was “conceived, written, re-written, re-re-written, and printed inside ten weeks”. This book, his most powerful work, is the account of a man torn between lofty impulses and primal instincts. Two characters in the story are complimentary and inseparable, Stevenson works up a fierce tension through a head-on confrontation between the two conflicting attitudes that oscillate between reason and passion, between savagery and civilization.

Dr Henry Jekyll thinks that he sits ‘beyond the reach of fate’. He is unsettled by the call of ‘leaping impulses and secret desires’, and invents a chemical that helps him, by way of providing disguise, keep his misdeeds unspotted from the world. Although not for long. His ‘love of life screwed to the topmost peg’ plunges him into deep trouble. Slowly but inevitably, he is robbed of his noble quality as his blind instincts hold sway. With too much of Mr Hyde and too less of Dr Jekyll in him, Henry finds himself a prisoner of his own black thoughts. He now sees nothing but abysses yawning all around him, and he ultimately succumbs to a surfeit of deadly forces within him. Stevenson, through this novel, succeeded in gaining access to penetrating insights into life, that both good and evil are inherent part of human nature. The character of Henry Jekyll anticipated numerous similar characters that were fashioned over the next few years, for example, Dorian Gray in The Picture of Dorian Grey (1890) by Oscar Wilde, Kurtz in Heart of Darkness (1902) by Joseph Conrad, Wolf Larsen in The Sea-Wolf (1904) by Jack London. Stevenson, before he could finish Weir of Hermiston, arguably his ‘finest work’, which was posthumously published in 1896, died of a brain haemorrhage on December 3, 1894.