It’s not widely known that once when struck by a tragedy–the sudden demise of his wife, just five years after his marriage—R. K. Narayan (1906-2001), the Indian writer par excellence, had decided to give up writing.

“The writer’s personal tragedy,” said Graham Greene, “has been our gain.” Greene couldn’t have been more right. Narayan’s self-imposed exile didn’t thankfully last for long. After a gap of few years, he wielded the pen once again, this time with a much surer and greater hold.

“To comprehend a nectar / Requires sorest need”, wrote Emily Dickinson. R. K. Narayan, who was particularly fond of the English language right from his childhood, and who is now reckoned as one of the major writers in the language, had once, in a university entrance examination (1925), failed in English. It was from then on Narayan dipped into English literature with a sort of mulish determination.

His father being a headmaster, no one did ever stop his frequent visits to the school library. With a voracious appetite, he devoured Scott, Dickens, Moliere, Pope, Marlowe, Tolstoy and Hardy. Also, his constant and never-failing companion was either Golden Treasury or Gitanjali. Along with his demanding reading schedule, he exerted himself full stretch to learn the craft of writing.

At the outset, he took up “themes centering around a moment or a mood with a crisis” with the style of a writer that was most appealing to him. He found, at first, his writing a bit stilted and closely modelled on the works of his favourite writers. But he kept writing with a certain doggedness of spirit.

His very first assignment was to review a book which he did after struggling for hours. And seeing his own writing splashed over the page quite overwhelmed him. Soon, The Hindu accepted a story written by him, against a payment of Rs.30.

Narayan’s first experience with love was through the pages of fiction. Narratives of amorous nature created in him a desperate longing to fall in love. With a stunning frankness, he revealed an incident in his memoir, My Days. One day he came across a girl (Rajam Iyer) filling her bucket with water from a roadside tap. The girl never did so much as throw even a casual glance at him, but Narayan fell immediately in love with her. Although his horoscope “indicated nothing but disaster,” Narayan and Rajam, after some initial hesitation, tied the knot with the approval of their families.

Narayan took to freelancing out of the necessity to run the family, while trying his hand at writing novels in his spare time. His close friend Purna, at the time of going to Oxford, took the manuscripts of Swami and Friends, the very first novel Narayan wrote, to find a publisher for the same. But it was summarily rejected by all the publishers he got in touch with. Naturally, Narayan was a very disappointed man. He asked his friend to destroy the manuscripts out of sheer frustration.

But then Graham Greene, who was denied the Nobel Prize for literature, came to his rescue. It was he who was responsible for convincing Hamish Hamilton to publish the novel. Narayan’s relation to Greene was somewhat like Joseph Conrad’s to Edward Garnett, the only difference being that Greene never imposed himself on Narayan as Garnett did on Conrad.

Recommended by none other than Graham Greene, a series of novels by Narayan was published in quick succession – Swami and Friends (1935), The Bachelor of Arts (1937), and The Dark Room (1938). Narayan later paid a personal tribute to Greene when he said, “I owe my literary career to Graham Greene’s interest in my work.”

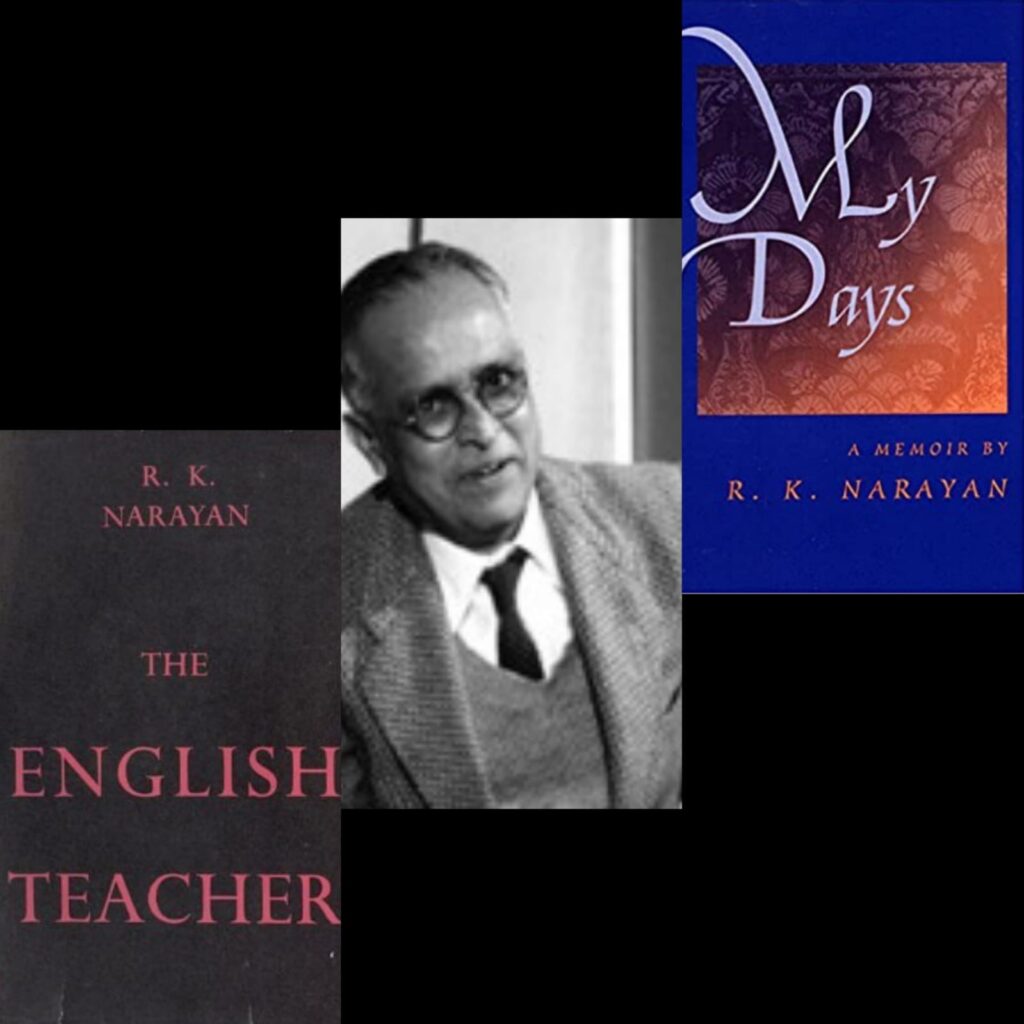

But any reader interested in the works of the writer would, perhaps, have noticed that his fourth novel, The English Teacher (1945), came out seven years after the third one was published. His wife when only 21 years old passed on in 1939. The tragedy almost robbed his will to ever put pen to paper again.

Looking at the tongues of shooting flames from his wife’s burning pyre, Narayan was a broken man, disillusioned with the ways of the world: “There are no more surprises and shocks in life, so that I watch the flames without agitation. For me the greatest reality is this and nothing else. Nothing else will worry or interest me in life hereafter.”

Narayan suddenly lost all his hopes and ambitions. His only desire was to somehow come to terms with the anguish. “Let life do its worst…”, he wrote in his semi-autobiographical novel, The English Teacher, “Every shred of memory will be destroyed, I will avoid torment thus …” How often he said to himself, “A long dip in this river, or a finger poked into a snake hole–there are two thousand ways of ending this misery.” When Narayan was buckling under the terrible weight of his grief, a miracle occurred. Raghunath Rao, a friend of his cousin, brought about a change by initiating him to a séance session.

Narayan was to say later in his memoir My Days that through a kind of telepathy he caught the message of his dead wife, who, in each of the sessions, exhorted him thus: “Until you can think of me without pain, you will not succeed. Train your mind properly and you will know that I am at your side.”

For quite some time, Narayan kept on attending these sessions and, in the process, “attained an understanding of life and death.” His efforts to keep the flood of painful feelings at bay bore fruit at last. He was once again inspired to take up writing and the outcome was The English Teacher – a work of great artistic detachment.

He also went on to create masterpieces like The Guide that fetched him the Sahitya Akademi Award, The Financial Expert for which he received a Filmfare Award, My Days that won him the English Speaking Union Book Award, not to lose sight of his other novels and stories set in the fictional town of Malgudi. He was honoured with the Padma Bhushan & Padma Vibhushan for his contribution to Indian literature, also a recipient of AC Benson Medal from the Royal Society of Literature.

Like Yoknapatawpha County invented by William Faulkner and Gondal by Emily Bronte, Narayan brought into existence the town of Malgudi about which William Walsh, a critic and admirer of his works, said: “Whatever happens in India happens in Malgudi and whatever happens in Malgudi happens everywhere.”